By Chris Finnie

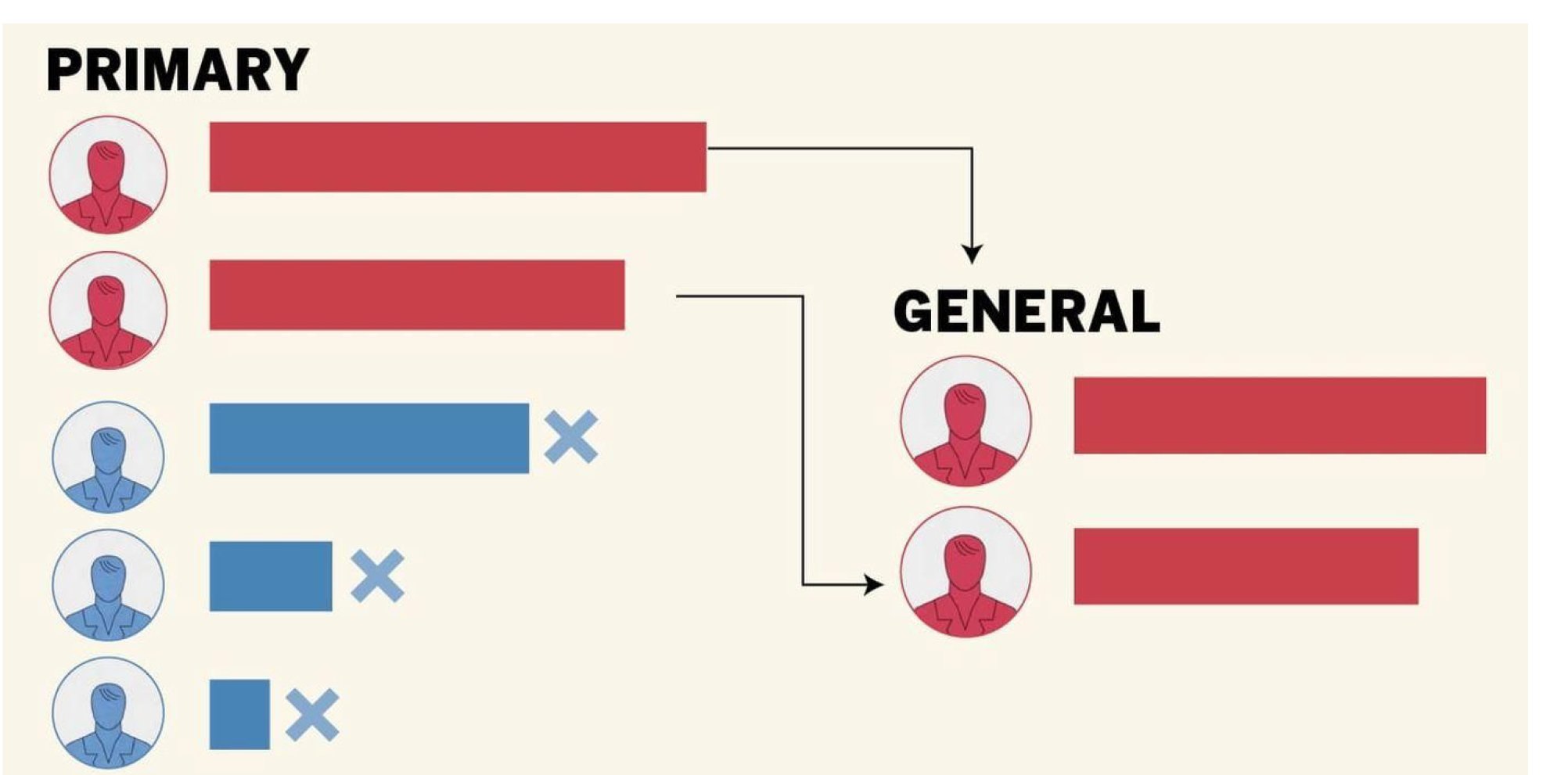

What was the effect this year of the state’s Top Two Candidates Open Primary Act, otherwise known as the “Jungle Primary,” which took effect in 2011?

In district 8, two Republicans are the only choices for the House of Representatives. For U.S. Senate, the only candidates will be Democrats. That’s also true in congressional districts 6, 27, and 44. If you’re a straight-line party voter in any of those districts, you may not have that option in November if your party’s candidate didn’t finish in the top two.

But, if you’re a third-party voter, your choices are even more limited. A “no-party preference” candidate will be on the ballot in only districts 5 and 20, and Green Party candidates made it to the top two just in districts 34 and 40.

Is Write-in Voting an Option?

Technically, you can write in a candidate. But only in the primary. In November, write-in votes will not count. To make things even tougher, write-in candidates need to file with the state before the primary. To file, 55 people need to sign a petition for a nominee.

There are a few exceptions to the law. The Secretary of State’s office says, “The Top Two Candidates Open Primary Act does not apply to candidates running for U.S. President, county central committee, or local office.

The Law of the Jungle

There are a number of ways in which this primary system changes electoral politics in California. While the June primary ballot contained an astonishingly huge number of candidates for many races, the November general-election ballot will feature a relative paucity of choices. Plus, some people tried to vote strategically for who had the best chance of making the top two, rather than who they really wanted.

It also makes it a lot harder for candidates to get on the ballot. With four, six, ten or more candidates running for some offices—sometimes even from the same party—it’s difficult and expensive to make it in to the top two. Again, that’s especially true for independent candidates in our expensive media markets.

This increases the influence of big money in the primary races. However, it decreases the influence of statewide political parties because they no longer have their own primary selection processes.

From my perspective, while the effects of this law are mixed, the narrower choices in the general election and more expensive primary races outweigh the positives of more grassroots involvement and less state party control. For example, in one Orange County race, The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee spent millions, including $400,000 on ads backing Rouda, who some party leaders felt was better positioned to defeat Rohrabacher this fall. That set up a clash with the state Democratic party, which endorsed Keirstead.

If you’d like to learn more about exactly how California primaries work now, you can go to the Secretary of State’s page about it at http://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/political-parties/no-party-preference/#top-two-candidates.